REciprocity

When we engage with others, whether to play, talk, learn, or teach, we take on different roles. The root word for “reciprocity” is to receive. The dimension of Reciprocity is trying to capture the giving and receiving within an interaction.

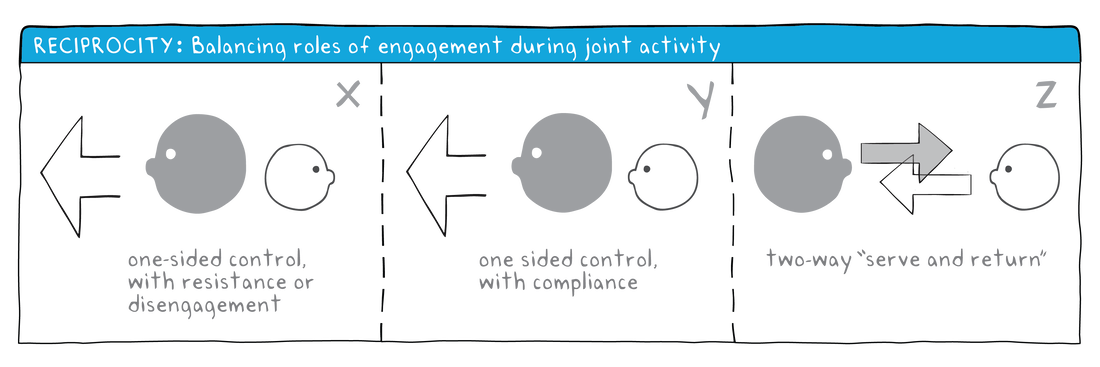

We identify three common modes of the roles of engagement in joint, reciprocal activities.

Note: For both X and Y, a child can be the one doing the one-sided direction as well. As one of our colleagues often says, “Don’t be stuck on the sizes of the heads”. For those who use the tools for more general purposes (beyond adult-child), you can even consider all the heads to be the same size.

In cultures where individual agency and initiative are particularly valued, there is a tendency to prefer “child-directed” or “youth-led” interactions over “adult-led” or “adult-directed” ones. In fact, observational and assessment tools (e.g., classroom quality assessment, teacher evaluation) often assign higher scores to moments driven by children or students rather than adults or teachers. In our fieldwork and research, we find that it is developmentally necessary for children to experience diverse modes of interaction. Often, adults do have to lead and direct, even when children are resistant. Sometimes, children are quite happy to follow adults’ lead to learn and emulate. That is why we did not put a “child-led” illustration at the Z end of the dimension. Our analysis of engagement roles can go beyond ideologies (e.g., always youth-led or always teacher-led) and consider the specific activity contexts and situations.

What is important is not the particular mode we happen to be in at the moment, but how and why (developmentally) we move between the modes. That applies to all the dimensions as well.

We identify three common modes of the roles of engagement in joint, reciprocal activities.

- X: Interaction with one-sided direction from an adult and children resist or disengage.

- Y: Interaction with one-sided direction from an adult and children comply or engage.

- Z: Interactions where the adult and child(ren) share a balanced, reciprocal partnership (it is difficult to tell who is directing or who is following).

Note: For both X and Y, a child can be the one doing the one-sided direction as well. As one of our colleagues often says, “Don’t be stuck on the sizes of the heads”. For those who use the tools for more general purposes (beyond adult-child), you can even consider all the heads to be the same size.

In cultures where individual agency and initiative are particularly valued, there is a tendency to prefer “child-directed” or “youth-led” interactions over “adult-led” or “adult-directed” ones. In fact, observational and assessment tools (e.g., classroom quality assessment, teacher evaluation) often assign higher scores to moments driven by children or students rather than adults or teachers. In our fieldwork and research, we find that it is developmentally necessary for children to experience diverse modes of interaction. Often, adults do have to lead and direct, even when children are resistant. Sometimes, children are quite happy to follow adults’ lead to learn and emulate. That is why we did not put a “child-led” illustration at the Z end of the dimension. Our analysis of engagement roles can go beyond ideologies (e.g., always youth-led or always teacher-led) and consider the specific activity contexts and situations.

What is important is not the particular mode we happen to be in at the moment, but how and why (developmentally) we move between the modes. That applies to all the dimensions as well.

REciprocity in motion

|

|

|

|